The story of Ralph Edward Kephart

Company E, 17th Armored Engineer Battalion

Army Serial Number: unknown

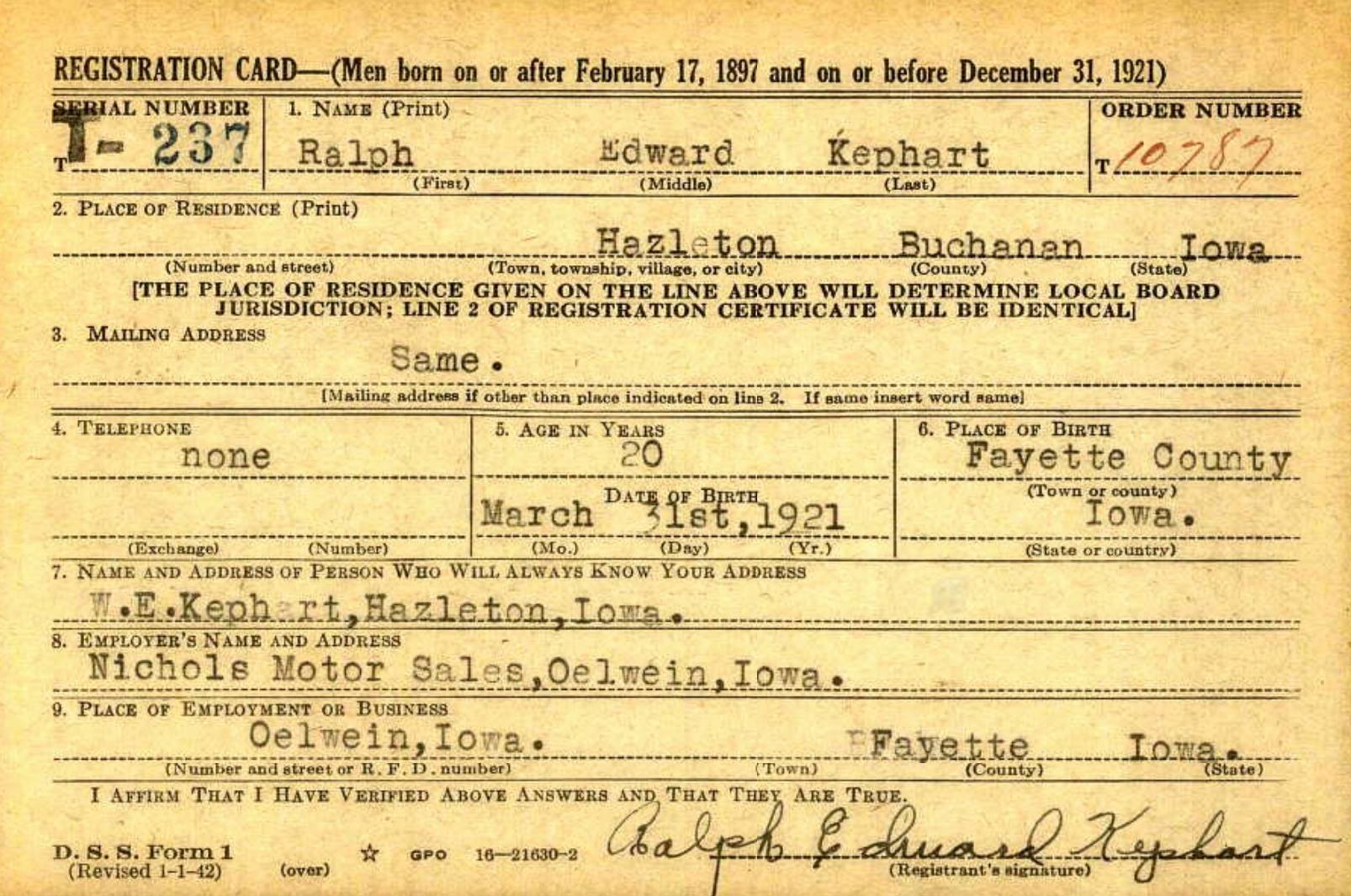

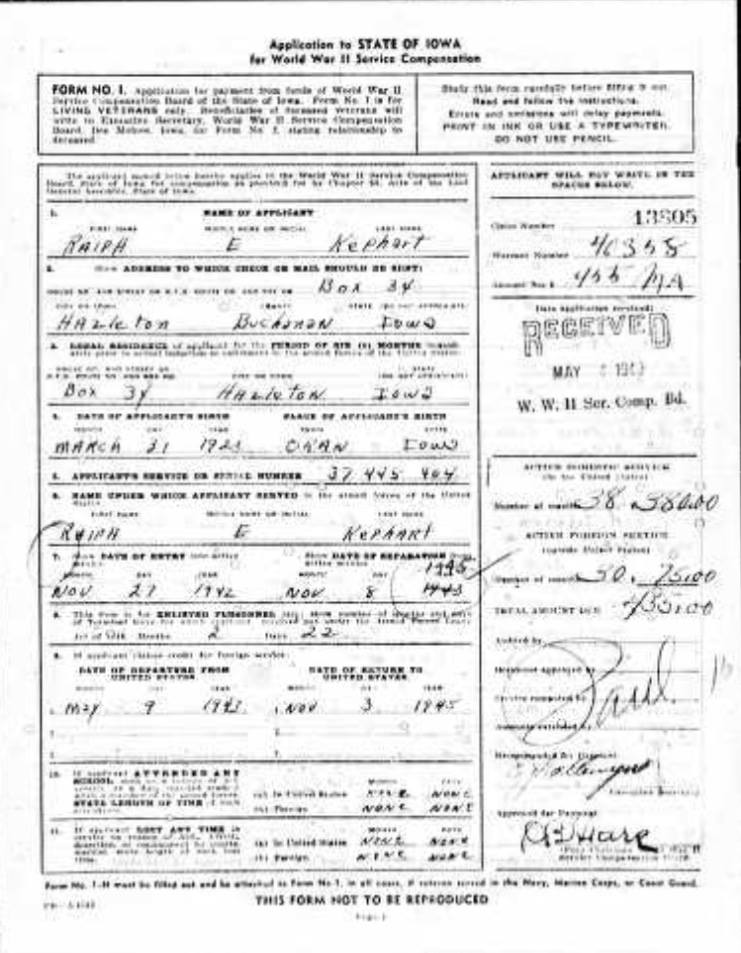

Born: 31 march 1921, Fayette – Oelwein, Iowa

Birth record

| Name | Ralph Edward Kephart |

| Event Date | 01 Jun 2001 |

| Event Place | Hazleton, Iowa, United States |

| Birth Date | 31 Mar 1921 |

| Address | Hazleton, Iowa 50641 |

| Address Date | 01 Jun 2001 |

| 2nd Address | Hazleton, Iowa 50641 |

| 2nd Address Date | 01 Sep 1998 |

| 3rd Address | Hazleton, Iowa 50641 |

| 3rd Address Date | 08 Jul 1974-01 Jun 2001 |

| Possible Relatives | Margaret E Kephart, Margaret Emma Kephart |

| Affiliate Identifier | 187445587 |

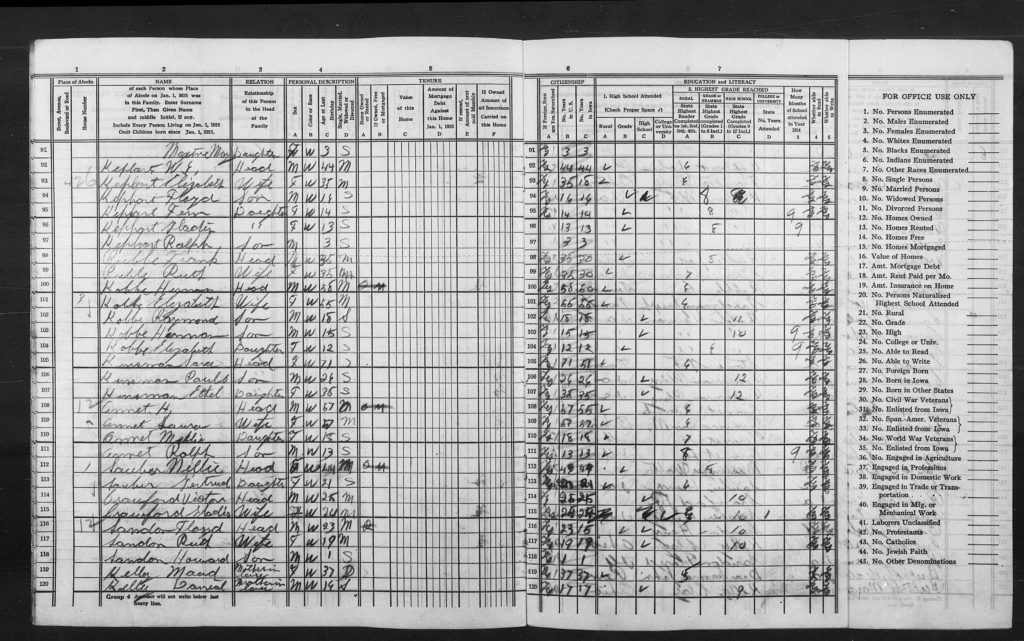

US Sensus 1925

| W E Kephart | 44 | Married | Head | 1881 | |||

| W E Kephart | ||||||||

| Floyd Kephart | Male | 16 | Single | Son | 1909 | |||

| Fern Kephart | Female | 14 | Single | Daughter | 1911 | |||

| Gladis Kephart | Female | 13 | Single | Daughter | 1912 | |||

| Ralph Kephart | Male | 3 | Single | Son | 1922 | |||

| Elizabeth Kephart | Female | 35 | Married | Wife | 1890 |

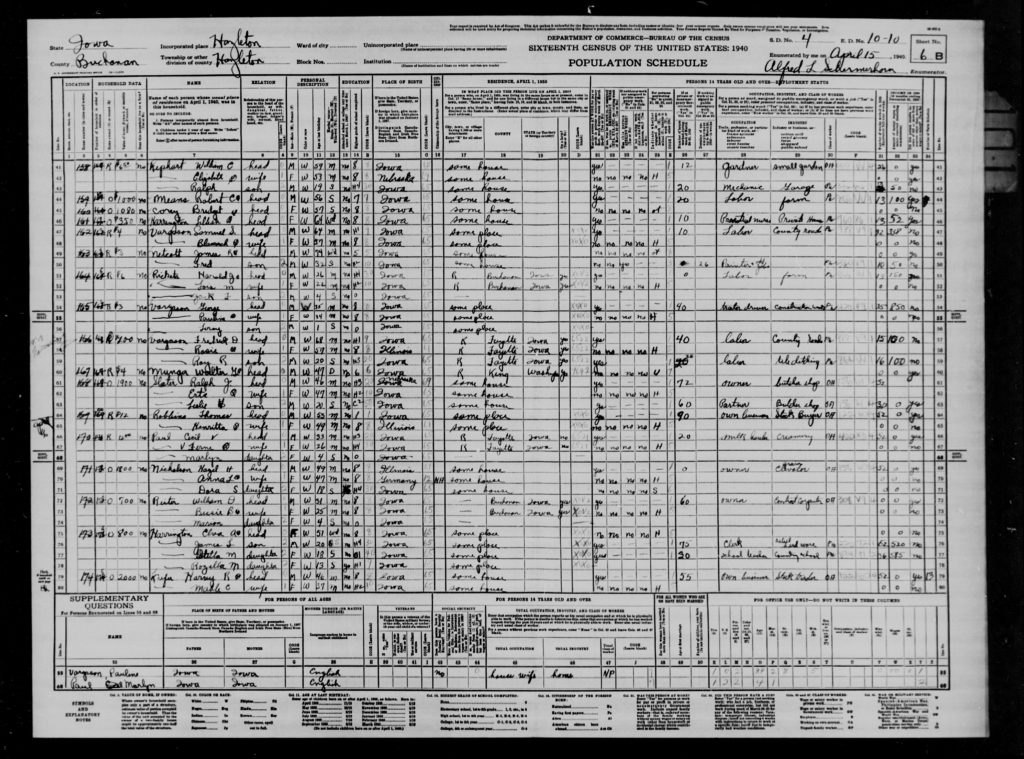

US Sensus 1940

| William C Kephart | Male | 59 | Married | White | Head | Iowa | 1881 | |||

| Elizabeth Kephart | Female | 53 | Married | White | Wife | Nebraska | 1887 | Same House | ||

| Ralph Kephart | Male | 19 | Single | White | Son | Iowa | 1921 | Same House |

Ralph was a Mechanic at a Garage in 1940 when he was 19 years old.

“07-2021”

Draft registration card

Ralph Kephart in his service uniform

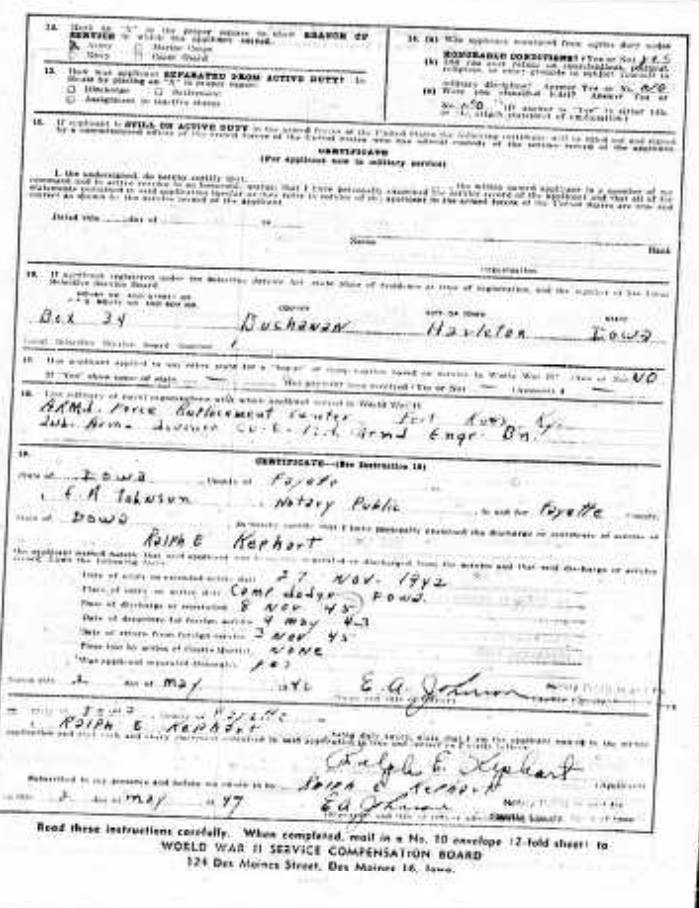

WW2 Compensation application

Interview: Kephardt The Courier

(Waterloo, Iowa, United States of America) · 15 Dec 2014

VETERAN

93-year-old remembers details of service in Europe

Fortunately, a few days after Kephardt and comrades were ordered into Belgium, the fog lifted, American planes hit the German positions and ground forces advanced, stopping the Germans short of their goal: seizing Allied fuel installations to keep the offensive going. German tanks and other vehicles were abandoned in the field, stalled and out of gas.“I don’t think the Germans thought they were going to win the war” at that point, Kephardt said. “But what they were trying to do was make a better peace give it one last push and maybe they could sue for peace” on better terms, as opposed to unconditional surrender.

But Kephardt said Allied leaders like Gen. Dwight Eisenhower and President Harry Truman would not have allowed the Nazi regime to remain in power and “weren’t going to settle for anything but unconditional peace The human slaughter going on in the Nazi concentration camps was becoming more widely known at that point. “We got into one of those camps.

We knew what it was. You can’t imagine what those Germans were doing;’ Kephardt said. “Now, the (regular) German soldiers were pretty nice guys and I talked with several of them. But I’ll tell you, the ones that were bad were those SS troops” who ran the death camps and made up some of the forces fighting in the Biller.The German defeat there allowed Kephardt and his comrades to resume their march into Germany and secure an Allied victory the following spring. Within the Second Armored Division, Kephardt served in Company E of the 17th Armored Engineers.

Their job was to place portable floating pontoon bridges at River crossings so troops and tanks of the 2nd Armored could advance into Germany. He entered Europe at Omaha Beach a few days after D-Day. Part of his job was running a generator that supplied the air pressure to inflate the large pontoons under the bridge deck.

They also plugged holes when pontoons were shot up by the enemy. Crews always kept their rifles near, he said.

Kephardt served three years in the Army, including service in North Africa and Europe, and earned six battle stars for the various campaigns he was involved in. His outfit received a Presidential Unit Citation for its quick work in setting up a bridge crossing of the Rhine River into the heart of Germany in March 1945.His closest call came a short time later, when German artillery shot up and sunk their bridge as troops were about to cross the Elbe River. Two companies of U.S. troops who had already crossed had to be retrieved by boat to be saved from the Germans. Many were. Some weren’t. During the artillery barrage,

Kephardt and a buddy, taking cover under their trucks, decided to make a break for a stone house they thought would provide better shelter. “We got to the door of that house, and an explosion blew us both right into the house. In fact, it blew me over the top of him;’ Kephardt said.

“We stayed in that house and they hit that house two or three times and we decided we’d better get out of there. They and two other comrades taking shelter grabbed a truck and escaped. Kephardt said he took a piece of shrapnel in his head but never sought a Purple Heart. “It didn’t hurt me. It just burned,” he shrugged. “That was the worst deal I ever got into. They just blew hell out of stuff!” His unit withdrew several miles to be re-equipped and returned to the same crossing, only to now find it occupied by Soviet troops who had advanced upon the Germans from the other direction.The war was over. Kephardt recalls the presumed Soviet allies to be less than hospitable. “They weren’t too friendly” he said. They denied the Americans a crossing at that point on the Elbe, forcing them to ford at another location. Also, Kephardt recalls being stuck in American sector of Berlin at the war’s end for several weeks when the Soviets blocked a main road out of the city. Kephardt, a lifetime mechanic and retired instructor at Northeast Iowa Community College in Calmar, is a very healthy 93-year-old. Born in nearby Oran in Fayette County, he has lived in Hazleton since 1933, save his military years.

Source: Kephardt The Courier (Waterloo, Iowa, United States of America) · 15 Dec 2014)

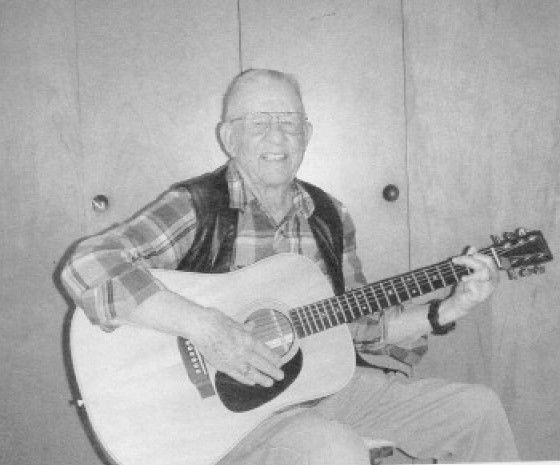

He loves to tinker with computers, play guitar and electric bass and carve wood. He and wife Margaret both still drive and travel. Widowed and remarried, he has two sons, living in Cedar Rapids and Minneapolis, and several grandchildren. Some effects of his military service are apparent. He used to startle easily from sleep, and Margaret says he’s still a light sleeper. When he returned from service, he told his mother never to touch him to wake him, only to call him, because he didn’t know how he’d react. Though names fade, he still recalls his brothers in arms.

He was given a chess set by a friend in North Africa who taught him how to play. That buddy told him to keep it until he saw him again. Kephardt still has it. He also recalls a buddy in Europe who nursed him back to the health and kept him fed for several days when he took deathly ill. “I’ll tell you one thing: Nobody can believe it unless you’ve done it.

Nobody can believe how close you can get to another guy Kephardt said. “You get pretty close to a guy, see. You get awful close to somebody else because that’s all you’ve got!’ Then there was the Dutch family Kephardt and his friend never got to share Christmas dinner with.

But the family’s gesture in itself was an expression of gratitude for something even more precious the American soldiers shared with their hosts: freedom.

Read more about the Elbe river crossing here: Treadway bridge ” Roosevelt Bridge” across the “Elbe river”, at Westerhusen, Germany on April 13-14, 1945

“07-2021”

Interview recording, The Grout Museum District

Kephart_Ralph_kiosk_70818.mov from Grout Museum District on Vimeo. Source: groutmuseumdistrict.org

More about the Pontoonbridge crossing across the Rhine that Mr Kephart tells about in his interview: 1945 March 24, at Spellen, Germany, Bridging the Rhine

“07-2021”

HAZLETON – Ralph Kephart will celebrate his 100th birthday on March 31. A World War II combat veteran of the Battle of the Bulge, Kephart is excited about watching from his living room window as friends and neighbors “drive by and honk” from 1 to 3 p.m. March 27. His sons, Ralph Jr. and Dean, also have asked folks to send Kephart a birthday card in time for his centennial birthday. They’d like him to receive 100 cards.

Melody Parker Mar 20, 2021 Updated Apr 25, 2021

“My legs don’t work so good anymore, so if anybody drives by and honks, well, I’m happy to sit here and wave at them. I’m not so sure what to do with 100 cards. I’ve already got 25 of ‘em,” said Kephart, who otherwise is healthy. He lives on his own and eats “pretty much” what he wants.

“I love pizza. When Ralph comes, he brings a pizza. Maybe he’ll bring one for my birthday. That’s all right with me. Dean’s supposed to come down, so whatever they want to do is alright with me.”

Dean Kephart, of Minneapolis, describes his dad as “a very social guy with lots of friends. We wanted some way to celebrate his 100th birthday in a way that would be safe in times of COVID-19. That was number one. We felt like a gathering was inappropriate, so we sent out postcards and used social media to see if we can get the 100 cards and people driving past and waving. If it’s a nice day, he could be on the front porch.”

Born in Oran, Ralph Kephart’s family moved to a 20-acre vegetable farm near Oelwein before moving to Hazleton, where he has lived since 1933. At 17, Kephart worked for the Civilian Conservation Corps helping to build Backbone State Park near Strawberry Point. He went into the U.S. Army a year later, serving as a combat engineer with Company E, 17th Armored Engineer Battalion in the Second Armored Division during World War II.

He landed on Omaha Beach in Normandy several days after the D-Day landings. His battalion’s job was inflating large floating pontoons used as bridges for the armored division to cross rivers as it advanced into Europe. He also saw action during the Battle of the Bulge, a major German offensive campaign from December 1944 to January 1945 in the forest region of the Ardennes in Belgium and Luxembourg. Kephart served for three years in Europe and North Africa and received six battle stars.

“World War II was a long time ago and sometimes now it’s hard for me to remember all the details, the names and stories,” the veteran said. After the war, the soldier returned home and worked as an auto mechanic and later taught auto mechanics at Calmar’s Vocational-Technical School, now Northeast Iowa Community College. He also completed his college degree.

“I’m still a car guy at heart. I still like to get out and drive,” Kephart said. He’s a familiar face at the Burger King in Independence and McDonalds in Oelwein where he drives for lunch. His legs began to fail several years ago after a bout with pneumonia. Now he rides an exercise bike daily in the winter to keep fit and rides around town on a three-wheel bike during spring, summer and fall.

“What I like to do is find some people I can visit with – that’s one reason I ride is so I can see someone along the way and stop and talk. I lost my second wife two or so years ago, and it’s pretty doggone lonesome,” Kephart explained. He married his sweetheart, Margaret Solomon, after dating her for six months. She was a first-grade teacher at Hazleton Elementary School until her retirement. They had two sons and several grandchildren. She died in 1999 after battling cancer. Throughout his life, Kephart has enjoyed wood carving, using his lathe to turn candlesticks and bowls and making wooden toys and other pieces. He tinkered with televisions and CB radios and still loves technology, especially computers.

“He is a man of amazing curiosity and explored many emerging technologies and hobbies,” said Dean. “Two months ago, I bought him a handheld audio recorder and gave him two pages of questions from his earliest memories all the way through. I thought it would keep his brain sharp.”

A member of Masonic Lodge, Kephart served on the Hazleton town council and was a member of the volunteer fire department, as well as superintendent of Sunday School at his Methodist church. Other hobbies included golf, archery (making his own arrows) and bowling. He also played guitar, bass guitar and harmonica, and he sang in a band.

“When I was a child, he and the band would play dances nearly every weekend. I think he cleared something like $25 a night. I remember being woken up backstage and carried to the car when the dance was over. In retirement, he and the band traveled to more than 17 nursing homes across Northeast Iowa to entertain the residents,” Dean recalled. His mom was the band’s booking agent and played autoharp.

For many years, the Kepharts organized a hootenanny that drew hundreds of people every Friday night at Hazleton’s American Legion Hall. Margaret was responsible for all the food shared at the end of each evening.

Kephart married again in 2000 after meeting Margaret Prahm at the Hazelton Post Office, although she’d lived down the street from him for many years. She passed away two years ago.

When asked about his own longevity, Kephart laughed. “I don’t know why I’ve lived so damned long. I can’t tell you why I’ve lived longer than anyone else in my family. I really didn’t take care of myself – smoked until I was in my 60s and just lived my life. I think it’s because the Lord thinks I’m an ornery cuss.”

Research 2020, updated 07-2021: Stefan Mandos, Martijn Brandjes